|

|

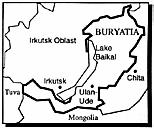

"The swan is our mother and the birch -- our family tree," say the old Buryats. The Buryat Chronicles start with a legend about a hunter who sees wild swans take off their swan dresses and turn into beautiful girls. He steals one of the swan dresses, while the girls are swimming in Lake Baikal. Startled, most of the swans fly off, leaving one behind to plead with the hunter to give back her dress. Yara Arts Group, which I head, included this legend in our newest piece, Virtual Souls. We also worked with Vladlen Pantaev, a Buryat composer, last spring at La Mama. As a result, we were invited by the Buryat National Theatre to work on the project in their theatre in Ulan Ude last summer.

|

|

Selenga River near Ulan Ude

Selenga River near Ulan Ude

I traveled to Ulan Ude in the beginning of August with one Yara actor, Tom Lee, who helped me conduct the workshops with the Buryat actors and prepare the way for the five Yara members who joined us in the middle of August. Vladlen Pantaev, Tania, his wife, the Buryat actors, and their friends met the two of us at the airport. After sprinkling some milk and vodka, a shamanist custom that would be repeated on many occasions, we drove off into the countryside. We had arrived just in time for a great occasion -- the blessing of the corner stone for the first datsan, Buddhist temple, to be dedicated since the Revolution. In the steppe stood a ger, a traditional round felt tent. It was filled with grandmothers. We squeezed in. The monk chanting looked familiar. Later I realized I had seen him in a picture standing next to the Dalai Lama. The chanting continued for the next several hours. Light streamed in from the top of the tent. I felt the centuries merge and expand. A thousand years ago things were done exactly this same way. Then a Russian soldier in uniform entered. You could taste the sudden tension. But he sat down in the exactly correct position and pulled out a lotus flower. A soft sigh escaped from the congregation. It was only a novitiate out to prove he had learned his lessons well.

Suddenly everyone in the ger got up and ran into the steppe. We followed the crowd into a construction site. A blue silk scarf was placed in a hole dug for the cornerstone. We were told to throw in coins for good luck. We searched our pockets only to find two New York City subway tokens. Some archeologist is going to be wondering about the significance of that someday.

Next morning we met the three actors we were going to work with at the theatre. Erzhena and Sayan Zhambalov were a married couple. They were the young stars of the Buryat National Theatre. A few years before they had walked out of this theatre and only recently had been convinced to return. They had organized their own shows and also a band, Uragsha (Forward) which was at the forefront of a resurgence of pride among young Buryats. The third person we worked with was Erdeny Zhaltsov, who was both an actor and a musician. He played the morin kuur, the horse-head fiddle, a two string traditional instrument that can sound like a cello. After the introductions Erzhena spoke to me directly in Russian. (Usually at the theatre they speak Buryat which is related to Mongolian.) I answered in Ukrainian. We understood each other. We were all very relieved. It is so hard to work through a translator. I told them about the show. Afterwards she told me that their cousin, who was 18, had been a soldier. His body had arrived that morning by train from Chechnya. We decided they should go home and take care of family matters. Tom and I would see the area.

Tom Lee, Virlana Tkacz, and Tanya Pantaev at the Ivolginsk Datsan

Tom Lee, Virlana Tkacz, and Tanya Pantaev at the Ivolginsk Datsan

We walked around Ulan Ude that day. The main square is lined with crumbling Soviet-style buildings. In the center, alone on a pedestal, is the largest head of Lenin in the world. At over four stories high, this surreal monument towers over the town. The other unusual site is a surprisingly beautiful opera house. The locals told us it was constructed by Japanese prisoners of war in 1953 and did not seem to think it was strange that Japanese prisoners of war were still being held in Siberia eight years after the war.

We also drove out to the Ivolginsk Datsan, a Buddhist monastery at the foot of the Khamar-Daban Mountains. It held out as the center of Buddhism in the USSR after 37 datsans and 10,000 monks were destroyed in the 1930s. Much of the art work from the destroyed datsans is preserved in Ulan Ude in what is known as the Fond. The Fond was originally established as an anti-religion museum under Stalin, but in this guise it preserved the thousands of Buddhist sculptures, tankas, vestments, banners, musical instruments and sacred volumes that now line it shelves. But the Fond's future is now in jeopardy. It is housed in a former cathedral and the Orthodox Church is demanding that the building be returned. No other location has been found to house the collection.

Next morning Valentina Dambueva came to our rehearsals and sang her heart out. Known as the best folk singer of Buryatia, the diva cooled herself with her fan, flashing smiles that set her gold teeth glistening in the sun. We said "wind" and she sang three amazing songs, then we said "swans" and heard even better ones. The three Buryat actors translated the meaning of each song into Russian. We would then confer as to where in our piece such a song might fit. Virtual Souls is mostly sung. It tells its story through a series of traditional Buryat songs and contemporary ones we've written or found. The original score is created by Genji Ito and combines both traditional Buryat instrumentation and contemporary music created with a sampler on a computer. When we agreed that a particular song was of interest, the Buryat actors would note the words and music, not an easy task given the traditional style of singing does not lend itself to standard music notation. Then they would translate the words into Russian and I would take notes in English. Later Tom and I could work on an English translation you could sing to the notes. This method of work was both exhausting and very rewarding since in the process we learned a lot about the Buryat music and the possible direction in which we could develop our piece. It also provided our piece with a very special sense of cultural authority that was immediately recognized by the people who saw it in Ulan Ude.

Before we could start rehearsals we also had to translate our script into Buryat. Our actors play New Yorkers plugged into the Web devouring information about everything and anything on the superhighway. They fall into a mythic past by opening up the Buryat Chronicles where they learn to recognize the spirit in the presence of things. We wanted the Buryat actors to speak on stage in their own language and the Yara actors to perform in English. Before this could happen smoothly we had to translate into both languages everything that was said, so that the partners could play the scenes and coordinate proper responses. Since our theatre pieces are developed in rehearsal the script is always evolving and the transaltions had to be constatnly updated. It is also very important for us to include into our piece the responses of the local artists and to have their performance material come from them.

Erdeny, who played the bard, suggested that we include the traditional introduction that opens every Buryat tale. He sang it, accompanying himself on the horse-head fiddle.

Then he started to do throat singing and Sayan joined in. This is a

traditional style of singing in which the voice is located in the

throat and one singer can produce two distinct sounds simultaneously.

Could this fit into our text, he asked? Yes, of course, we loved it.

I asked him to write out the lyrics, so I could put them into the

script. Erdeny did not believe that I would be able to type in Buryat

or that my computer could print it. But after some coaxing he sat

down with a pen and a pad. Erzhena translated the words into Russian

and then I worked on the English translation. That night I sat at my

computer first typing out the English, then stumbling with the

Russian and finally pecking out the Buryat letter by letter. Next

morning I handed out the scripts to an absolutely quite room. Then

Erzhena started laughing, "You know, I couldn't imagine how we were

going to do this -- you speaking English, the three of us speaking

Buryat and everything changing everyday because we are still creating

the piece. But you hand me this and suddenly it all seems very

possible. Why don't we work on my part today."

When later my printer ran out of ink and the backup cartridge I

brought turned out to be dry, I couldn't believe my bad luck. I had

to continue updating our script every day. We were still writing new

sections in our play. I had to provide the actors the new versions

with parallel translations before they could rehearse the scenes. The

person who especially needed a current script was our slide

projectionist, a brave 14 year-old who was not intimidated by

technology. He had to figure out how to show the 150 slides in our

piece in the proper spots and his knowledge of English was extremely

limited.

The situation with the printer looked hopeless. The selection of

Western goods in town was limited mainly to brands of chewing gum and

I needed a Canon jet cartridge. I stopped in all the places that had

anything to do with electronics. People were trying to sell me all

kinds of things that couldn't possible fit any printer, much less

mine. Then I saw a salesperson, who was actually using a computer. I

asked him where I could get the cartridge I needed. He checked me out,

glanced around and then whispered: "In the hunting store." I thought

he was kidding. But he drew a map on his card and told me to show it

in the hunting store. I did so and was led into what looked like a

yard shed. An old man opened the door. As I followed him down the

stairs my heart was beating so hard I could hardly breathe. What was

I doing here alone asking about computer equipment. Our hosts were

always warning us about the criminal elements in town. When I got to

the bottom of the stairs, there was a huge storeroom of computer

equipment. I asked for the cartridge by number, the woman pulled it

out. I had to sit down to catch my breath.

Erdeny Zhaltsov playing the morin kuur in Virtual Souls

photo by Watoku Ueno

Erdeny Zhaltsov playing the morin kuur in Virtual Souls

photo by Watoku Ueno

It was long, long ago

In the good old days

When the grass was always green

When the blue sky was just being conceived by the universe

When the birds first learned to sing

Yes, it was then

When the great mythical bird was just a chick

Yes it was then

I felt it was very important that we rehearse our piece on Lake Baikal, where the mythic sections take place. Once all the Yara actors arrived, we piled into a tiny bus and left for what the Buryats call the "sacred sea." Lake Baikal is the deepest body of fresh water on earth, and contains one fifth of the earth's freshwater supply. The water from its center is so pure that is becomes contaminated by the glass of the laboratory beakers. The lake is renown for its sudden changes in weather. An American wrote: "It is only on Baikal in the autumn that a man learns to pray from his heart." But the Buryats pray to the Baikal and to all of nature throughout the year. As we rode to the lake we often stopped on a hill, or in a spot where the steppe suddenly opened up, to sprinkle milk and vodka and to thank the masters of the landscape. The Buryats say, "People ask us where is you church architecture, and we say we pray in a church where the dome is the sky and the foundations are the earth." Nature is spectacular there, truly awesome.

We rehearsed our show on the shore. In one scene the actors say their

own addresses starting with their present address and stepping back

to say the previous one. They experience the place and themselves at

each address. After reciting their place of birth, every actor

stepped into the waters of the Baikal. Yes, we were all floating in

water before birth and life on earth began in the seas. We still feel

its pull today.

On the way to the Baikal we also bought a sheep that was put on the

bus with us. When we got to our campsite the bus driver, a 23 year

old with graying hair appropriately named Bayar Timur (in Buryat

"warrior of steel"), slaughtered it. But this was done very

differently than I ever imagined it. He swiftly cut a small incision

in the lamb's chest. Then, as we held its legs, he put his hand into

the cut and snapped an artery to the heart. The sheep died almost

instantly. He held his hand to its face. It all seemed so humane,

that even the one vegetarian in our group ate with us that night.

On the way back there were many stops to visit with our hosts'

friends and family. The most amazing one at "grandma city," a maze of

huts and rooms in which Tania's mother's lived. She was easily in her

80s. As we sat down to a feast, Erzhena sang her a Buryat song in

thanks. Then Cecilia, who is a Californian of Armenian-Peruvian

heritage, asked if she could sing. She sang the same song she had

sung to her own grandmother -- "Forever Young" Erzhena and I

translated. The grandma wiped her tears and said she had no intention

of ever aging another day and gave Andrew, one of our actors who was

in his 20s, a great big hug. Everyone laughed. Then, she held his

face and said "God, you look just like one of my own." And Andrew who

is of Korean heritage certain does look like her son. The Yara actors

are a multicultural group of artists and often local people refused

to believe we were American. But our diversity also opened many doors

for us in a culture that had become closed to outsiders because of

the disrespect it has suffered.

Cecilia Arana, Zabryna Guevara and Eleanor Lipat rehearsing on Lake Baikal

photo by Virlana Tkacz

Cecilia Arana, Zabryna Guevara and Eleanor Lipat rehearsing on Lake Baikal

photo by Virlana Tkacz

Eleanor Lipat, Cecilia Arana, Zabryna Guevara and Erzhena Zhambalov as Swans in Virtual Souls

photo by Watoku Ueno

Eleanor Lipat, Cecilia Arana, Zabryna Guevara and Erzhena Zhambalov as Swans in Virtual Souls

photo by Watoku UenoThe last section which we developed for our piece in Buryatia had the actors play themselves in a rehearsal. In this scene the Buryat actors tell local variations on the swan story as they teach the Yara actors to play a traditional Buryat game with sheep bones. When Erzhena told of how every dawn Buryat women still sprinkle milk into the sky, a white offering, a prayer for the return of the great white bird, Tom asked her if the swans ever appear at that moment. "Oh no," said Erzhena, "there are no swans here." We couldn't believe it. Swans are the symbol of Buryatia. Their pictures are on everything. Then Erzhena told us there haven't been any living swans in Buryatia for hundreds of years. "These are dark times, but we believe that when the time is right, the swans will return to Buryatia."

We performed Virtual Souls at the Buryat National Theatre on

September 7, 1996 as a work-in-progress. Many of the actors from the

troupe came, as did the present and the past artistic directors of

the Buryat National Theatre. Valentina Dambueva was there and

afterwards told us how wonderful it was to hear our actors sing her

songs in English and to imagine that now they could be sung in New

York. There was also a large group of students from the Technical

Institute who were studying English.

Tsyden Zhimbiev, the writer of Buryatia, also saw our show that night.

After the show Sayan came up to me and said Mr. Zhimbiev wanted to

see me next day. We met the old writer in his office. He told me I

had to change a few slides, since some of the ones in the production

were not of real Buryat petroglyphs. Then he gave me a rare out-of-

print book on the topic. We had a long conversation about the show

and I strongly felt I was on the inside now. He said he thought that

we had done something very important. We had placed Buryat culture in

a modern context yet allowed it to sing in its own voice.

Cecilia Arana and Tom Lee in Virtual Souls

photo by Watoku Ueno

Cecilia Arana and Tom Lee in Virtual Souls

photo by Watoku Ueno

VIRTUAL SOULS in Siberia

VIRTUAL SOULS in Siberia